I recently read two short books of talks, columns, and essays by Umberto Eco, and their differences could not be greater. One is largely satirical or personal, and the other full of critical analysis of society. They do have in common Eco’s extraordinary erudition and wisdom and a consistent theme of advocating logic. Explosive flashes of epigrammatic brilliance smolder from the lines as they blister the pretensions and vacuities of modern life. Many of these columns were written from the 70’s up through the early 90’s, and likewise, the moral pieces were composed mostly before new millennium – though most of the insights and commentary remain timeless. For decades, Eco wrote columns for newspapers and the news magazine L’Espresso, and the first book is a collection of selected columns.

While his novels are often witty and satirical, like Foucault’s Pendulum, they are not often funny in the manner of provoking laughter. But reading excerpted columns from How to Travel with a Salmon[1] I laughed out loud, by myself, several times. I was, in fact, shocked at how funny some of them were. These columns are mostly on the topic of, or somehow related to, travel – and most of them are making vicious fun of bureaucracies. He also tackles common, even stereotypical, topics of travel gripes, like airplane food. Though this particular comedy cliché may remind the reader of the Seinfeldian-style of observational comedy (often stylized as “What’s the deal with airplane peanuts?”), his take is original and humorous. Many of these stories are autobiographical fictionalizations of Eco’s own extensive travel for his academic work, though some are pure fiction without the pretense of reality.

Here is one that is so good, entitled “How to Go Through Customs,” I want to include the entire opening paragraph:

The other night, after an amorous tryst with one of my numerous mistresses, I did away with my partner, bludgeoning her to death with a rare Cellini saltcellar. I was inspired not only by the strict moral code instilled in me since childhood, according to which a woman who indulges in the pleasures of the senses is unworthy of mercy, but also by an esthetic motive: namely, to experience the thrill of the perfect crime. I waited, listening to a CD of English baroque water music, until the corpse was cold and the blood had congealed; then, with an electric saw, I began dismembering the body, trying at the same time to adhere to certain fundamental anatomical principles, thus paying a tribute to our culture, without which refinement and the social contract would not exist. Finally, I packed the pieces in two suitcases of oryx hide, put on a gray suit, and caught the wagon-lit for Paris. Once I had handed over my passport and a scrupulous customs declaration to the conductor, listing the few hundred francs I was carrying on my person, I slept like a log, for nothing encourages repose more than the sense of having performed one’s duty. Nor did customs venture to disturb a traveler who, merely by purchasing a private berth in first class, asserted ipso facto his membership in the hegemonic class and thus his status as a person above suspicion. (pg. 23)

There is even a column that is in the form of an epistolary sci-fi story which satirizes our foolish tribalism and nationalism, and of course, government bureaucracy. Through these columns you really get a sense of his exasperation toward the everyday foibles of Italy, while also receiving his wariness of Italian political extremism (and the vacuity of Italian politics). Eco’s character pokes through the writing: at base he was an incessant intellectual laborer. Yet for all his relentless learning, Eco remains grounded in the mundane sorrows and strivings and joys of his life and retains self-awareness. Eco pokes fun at himself and his own voluminous learning in columns like “How to Take Intelligent Vacations” where he produces a “summer vacation reading list” that includes obscure medieval treatises on subjects like optics, and makes fun of his own status as literary celebrity and public intellectual in pieces like “Editorial Revision”:

On the other hand, after I ended a novel of mine with the verse of Bernard de Morlay beginning, “Stat rosa pristina nomine,” I was informed by some philologists that certain other extant manuscripts read, on the contrary, “Stat Roma,” which, for that matter, would make more sense because the preceding verses refer to the disappearance of Babylon. What would have happened if I had in consequence entitled my novel The Name of Rome? I would have had a preface by John Paul II, who no doubt would have made me a Papal Count. Or someone would have made a movie with Sean Connery in a toga. (pg. 178)

It is interesting to see what has changed and what hasn’t. Travel has changed in significant cultural manners, if not in substance, and the most notable change is probably in the culture of train travel. In America at least, train travel is almost exclusively used in commuting now, not a method of popular travel outside of inner-city movement. This is the context in which reading Eco now resembles looking into the past. Though more significant cultural changes can be detected in how he speaks about the people of the “Third World” and the “lower classes.” Eco does not self-censor, saying what he means to say, even if it would often be considered indelicate now. He seems to disdain political correctness for having the form, but lacking the substance, of acceptance and non-discrimination.

Eco was also a keen observer of the impacts of media and technology on society, particularly in the impact of television and the press on how we view the world, often noting how these mediums have disconnected us from reality. Eco is forever concerned that we stay within the confines of the real and corporeal – the human body is ever-present in his writing and is the touchstone of his ethics and fears.

In contrast to these columns are his serious reflections on serious topics in Five Moral Pieces[2], revealing a profound sense of fairness and an ethics grounded in those same deep-seated values of realism and inquiry.

The five moral pieces are: “Reflections on War” – written during the Gulf War, “When the Other Appears on the Scene” – Eco’s side of an epistolary debate where he defends a secular morality against a Cardinal, “On the Press” – a speech on the nature and characteristics of the modern press and its relationship with politics and television, the famous “Ur-Fascism” – a (now-famous) examination of the fundamental characteristics of Fascism, and “Migration, Tolerance, and the Intolerable” – an agglomeration of meditations about discrimination and fundamentalism. Eco sparkles when discussing the impacts of communications technology on the world, and on how we view the world. Fascism and war in Eco’s youth were not abstractions, but formative experiences, revealing the depth of illogic and inhumanity of which we are capable. Ethics, therefore, is no abstraction, but a tangible necessity of Eco’s conception of the life of the intellectual. And it is the life of the intellectual which is the core of all of Eco’s commitments. The embrace of rationality leads to wherever it may lead for Eco, but he is dedicated to this as the first principle of humanitarianism.

Eco’s commentary on the Gulf War acknowledges the changing nature of war in an era of global communications, and the changes in the perception and commentary on war those changes have themselves engendered. He maintains a steadfast opposition to war, no matter its perceived righteousness, as an intellectual imperative of humanity. War is now, by definition, all-encompassing in nature because of modern communications and transportation technology – it negatively impacts everyone across the entire earth, involved or not, opposed or allied to one side or the other, says Eco.

The complexity and interconnection of both modern war and the modern world ensures that clear goals can never be attained, and that, instead of war being a continuation of politics, politics is now a continuation of war. It is interesting that he should see this shift from Clausewitz’s “war as a continuation of politics” to “politics as a continuation of war” as a positive development, insisting that the morality of the Cold War, though full of its violence and injustices, was much preferable to the horrors of a hot war. This argument underscores his dedication to following the logic of his positions, and for maintaining a consistency in his anti-war view, despite the circumstances and nature of any particular war.

I cannot say that all of the essay holds up well, it is a certain reflection of the place and time of its writing and he grapples with the new realities of war appearing for the first time at scale in the Gulf War. Eco would probably be dismayed (maybe he was) by the de facto censorship in American media of the grim images of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. A large part of his description of modern war here involves the media being everywhere and not capable of being censored. In America the last 20 years, censorship (if not official) did exist, but perhaps more importantly, as a whole, the American people didn’t care about the wars, and they did not impact the “peaceful” economy. Burnout, which he says is the inevitable outcome of using new technology in his essay on the press later in this volume, impacted Americans in a way he did not anticipate. On the uncertainties of war, he is definitely correct, as recent events in Ukraine can attest.

The second essay, a letter to a Cardinal on the subject of the possibility of morality in a state of atheism, Eco explicitly draws a universal ethics out of universal principles that do not involve the supernatural. All global ethics can be derived, Eco argues, from merely understanding what causes pain for ourselves and our own bodies, and in the case of remorse, in our own minds. Freedom for ourselves, literal physical freedom from confinement, freedom to evacuate our waste and other basic, fundamental imperatives of being a living organism can inform how humans should act toward one another. This offers an almost mathematical axiom on the order of Euclid for human morality that perhaps a Christian would recognize: “what causes pain or discomfort to me must also cause pain and discomfort to other creatures like me.” A topic evolved in the humanism of the Renaissance, the focus on the human body, even with its unpleasant grotesqueries, is placed at the forefront of our lives and minds. This a stance almost like Rabelais, with the heightened focus on corporeality serving as a counterweight to the abstraction of the complex symbolism of modern societies. As a matter of fact, this argument could possibly be made in much the same way in a Rabelaisian voice of the early 16th century as it is here with the Cardinal. I’m not sure a civil debate involving the advocation of atheism would’ve been a cause for celebration to Martin Luther or Pope Paul III, but the form of the argument could be translated without difference. Eco’s argument is completely from logical precepts extending into a moral function, it does not require any knowledge of modernity or modern science. This has the value of displaying to us the power and force of logic, which does not need any props from scientific advances.

In Eco’s commentary on the press he delineates the impact that television has had on the newspapers, and, in turn, the impact the change in the focus of politicians to the medium of television has had on society. Television’s fight for the attention of the citizen and its tendency to be self-referential leads to more and more extreme divisions and a devaluation of intellectual discourse. The press is used as a tool of politicians instead of a tool of the citizens holding politicians to account. Any claim made by a politician gets repeated ad infinitum, until the actual substance and context is lost and the full control of content and opinion is in their hands. The delirious hunt for content and its incessant elevation of trivialities into scandals creates distrust in the reader and systematically destroys the authority of the press.

The loss of “authority” has initiated some of the most noticeable and drastic phenomenon of the internet age. If we don’t trust the news, and we don’t trust the government, and we don’t trust Church or school, where are we to find the organizing principles of mass society? Some would argue that we don’t need organizing principles, or that they can be localized, I would point to the forms of spontaneous organization swirling around us and disagree. We have to live in the context of our era, and the institution of the nation-state will not just dissolve, it will change, but it won’t disappear tomorrow. As long as we have any point of singular control (or overwhelming influence) for law, policy, wealth distribution, and the military as we do with our national governments, we will fight over the organization of society and form larger groups to achieve larger aims. Media in all its forms continues to influence social organization.

It is notable that the ever-increasing volume of printed media and television programming started to undermine authority before the internet was ubiquitous, according to Eco. As part of a natural process involving the specific types of competition that newspaper and television engaged in, the natural consequences led to devaluation of intellectual discourse and increased self-reference. At the end of this piece, after noting all these phenomena, which I think have generally held-up well, he does consider the future impact of the internet. Perhaps in this the complexity of the current situation was far too great to make predictions, but I think he makes a generally good point when mentioning the fact of information overload and how that could lead to a kind of renewal of gatekeeping by “educated elites” through the mechanism he calls the “censorship of excess.” This may be correct, except it doesn’t appear to be the “educated elites” who are curating the news so much as the complexity has created multiple, uneven centers of new authority.

“Ur-Fascism” is probably Eco’s most internationally famous work of non-fiction. In this piece he lays out what he considers to be the defining features of Fascism, the general rules of the functioning of the Fascistic society. He begins by recounting his childhood in Fascist Italy and defining Mussolini’s version of Fascism. Right in the second paragraph Eco states that “…freedom of speech means freedom from rhetoric” (pg 66). Later on in the essay, it becomes clear that what he means is that the fundamental lack of meaning contained in the constant rhetoric of Fascism, with Mussolini’s version as an exemplar, is restrictive of the free and open discourse which characterizes a democratic society. If words don’t represent ideas or reality, they confuse and stultify their hearers. This foreshadows his groupings of the features of the Platonic form of Fascism, which all involve the suppression of reason. Eco says that any single item on his list can be used as a basis to form a Fascist political group, but that the presence of any of these features does not mean a political movement is Fascist. I will list them briefly here, because who doesn’t love a good list?[3]

- The Cult of Tradition

- Rejection of Modernism

- The Cult of Action for Action’s Sake

- Disdain of Critical Analysis

- Exploitation of the Natural Fear of Difference

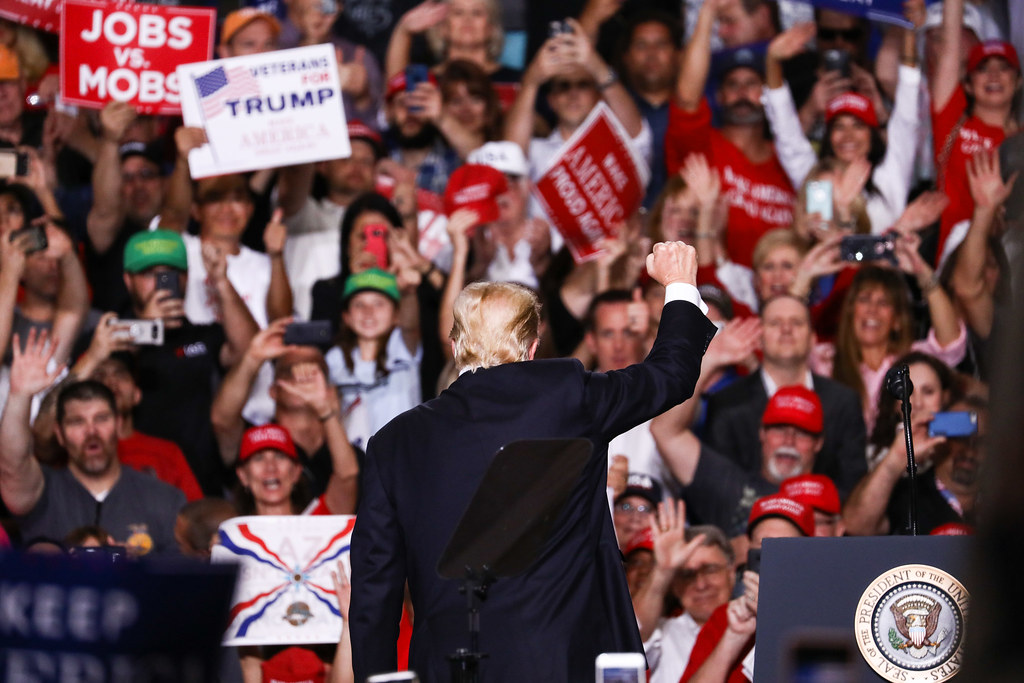

- Direct Emotional Appeals to a Frustrated Middle Class

- Obsession with a Plot/Group of Plotters

- Viewing the Plotters as Simultaneously Powerful and Weak

- Pacificism as Weakness/Life as Eternal Warfare

- Contempt of the Weak Combined with Popular Elitism (the common adherent is viewed as a member of the elite of society, regardless of their commonality)

- The Cult of the Hero/Cult of Death for a Heroic Cause

- Selective Populism (holding a minority of adherents to be the Vox Populi and acting as if they were the majority)

- Reliance on Newspeak (without a complex vocabulary, people cannot discuss complex ideas) (pgs. 78-86)

As the list lengthens, the natures of the features grow more interconnected despite Eco’s caveat that any of the ideas can be a source of Fascism. Starting with the cult of tradition, the heart of these ideas is that knowledge and rationality should be rejected in favor of the basic impulses of humanity. The idea of the cult of tradition that there is a profound and hidden ancient wisdom that exists and therefore there can be no new knowledge, flows logically to the next ideas of syncretic culture (since no new wisdom can be imagined), rejection of modernism (because the Enlightenment produced moral failure), the cult of action (because thinking is a product of rational enlightenment), and disdain of critical analysis (because that threatens the cult of tradition, since it is an illogical belief). The first four items, then, are all derived from the rejection of coherent ideology. Traditionalism is used to mask the fact that there is no intellectual content in the belief system, papered over instead by an uncritical syncretism which combines various aspects of previous ideologies despite any contradictions.

Exploitation of the natural fear of difference allows for the theme which connects the next few points. Amongst humans’ most primitive instincts is distrust of those not connected to their immediate social group. Education and complex ideas and institutions are necessary to allay this fear and allow broad cooperation, but it is always lurking deep in all of our minds. This primordial instinct can be used by those seeking power by appealing to a specific audience, enunciated in point 6, where Eco writes: “Ur-Fascism springs from individual or social frustration…” (pg. 81). It is a fearful middle class that is under economic distress or perceived disenfranchisement that wants to protect itself from those above and below in the social hierarchy. This is the nexus where conspiratorial thinking becomes the connecting principle between several of these points. The plotters and amorphous groups which are a threat to the adherents of the Fascistic political movement are forever hidden and resilient, unable to be clearly defined or destroyed, they serve as a perpetual tool to describe and animate the political movement and its supporters. Conspiracy theories are not falsifiable by nature (evidence against the conspiracy existing is taken as proof of a coverup or some other aspect of the conspiracy) and innuendo and association serve the purposes of evidence, and therefore can be used to justify anything, including the delusion of a minority being the majority, or that a person can be heroic fighting against a non-existent enemy.

Instead of a guide to the explicit nature of Fascism which it is often presented as, it can be read as a type of warning of the kind of features which an intellectually-degraded society exhibits. A Fascistic society is one in which logic has failed and the moral weight of the society has sunk to the level of the meanest individuals. Force and emotion have overcome reason. As in all things with Eco, one cannot escape the topic of semiotics, and this is perhaps one of his best examples in non-fiction where he incorporates this framework. Eco believes that cultural phenomenon are also signs, and therefore social and political movements can be understood through the functions of signs and the encoding of symbols. In the Fascistic society the symbols of politics and social organization are altered from a well-functioning, tolerant society by various types of cognitive distortions, by ruptures in logic. So rather than say, “these are fundamental aspects of Fascism,” I would say that a feature of anti-democratic and intolerant political movements is that their intellectual underpinnings are hollow. When you dig there is nothing there besides rhetoric.

There is something like the tendency of medical students to diagnose themselves with illnesses in the nature of the description of Fascism here. It is easy to point to almost any political movement and observe at least some of these principles, or even many of them. I think it is almost trivial at this point to equate Trump’s MAGA movement with these principles, since it conforms to almost every entry. This essay was popularly used to point this out at the time Trump entered the public consciousness as a serious political entity (look up Ur-Fascism on Google and at least half of the early results are articles using it to diagnose Trump/MAGA as Fascistic). I will not bother with that now but would point out that the list of ideological or rhetorical features are common around the world, in dictatorships and free societies. This is not to be dismissive, because in fact, it is fearsome. The endless appeal of conspiratorial thinking is its ability to form order from chaos and to relieve the believer of responsibility for their lives. As a political tool the appeal to irrational beliefs finds success in Brazil just as it does in Thailand, and has worked when it flowed from the pen of Marat in the late 18th century as it works in the production of video segments by Alex Jones in the early 21st.

Ur-Fascism packs a lot of explanations of organized human behavior in a small space. While it is sometimes abused to point beyond its intentions (and misquoted), it is right that it is so celebrated and reproduced. It also serves as yet another defense of intellectualism and science extending to morality, this time in the political realm.

In keeping with the theme of the dangers associated with politics in the previous two pieces, he focuses on the vicious impacts of intolerance on society, and the ultimate moral duty of the intellectual to frame our decisions using logic, instead of in animalistic tribalism and violence. First, he distinguishes between immigration and migration, with immigration being a controlled process that involves assimilation and migration being an uncontrolled process where entire groupings of humans move and bring their culture with them. Intolerance is easy in a society that controls immigration, as immigrants can be confined to ghettos, but intolerance becomes an ineffective stance when dealing with the overwhelming nature of migration. And, he warns with prescience, that migration is coming to Europe whether people like it or not, and that it will probably lead to violence. After the dislocations of the Arab Spring and Syrian Civil War, when migration from Africa and the Middle East caused severe social and political disruptions in the nations of Europe (and the tragedies of exploitation, internment, and the numerous instances of mass drownings visited on the migrants themselves), it is easy to place this essay in context of actual, historical events. It is no abstraction or idle musing of moral philosophy: intolerance is pervasive and harmful. Eco writes that intolerance itself can take numerous forms, and it is dangerous when it becomes a doctrine, a form of fundamentalism that will not allow dissent, and disables a logical appraisal of situations and circumstances. Combatting this intolerance with education is his solution, and also with laws where appropriate, but he warns that the expansion of intolerance into doctrine can become a political problem. No doubt the reference made here to a regime of fundamentalism in intolerance, where he says the wealthy theorize and the poor put into practice, is again referring to the danger of Fascism. Intellectuals must combat intolerance before the praxis of fundamentalism takes hold, because then it is too late.

Through Eco’s compendium of knowledge, we can almost see the ascent of humanity from ignorance and poverty to knowledge and wealth – and the errors that attended that transformation. We are still venal, and tribal, and vicious. In that aspect of humanity Eco, though an academic, is not naïve. He manages to say profound and piercing statements in every other sentence when taking up the mantle of a moralist as part of his duty as a public intellectual. In the form of the observational comedian he produces a mirror to reflect to us the absurdities and arbitrary roles and rules we’ve inflicted upon ourselves. What these pieces reveal about Eco himself is the strength of his powers of observation. His ability to distill the aspects of a thorny problem, or a feature of modern life, or a change in political communication to its most basic nature is extraordinary. Not quantitative, but based in empiricism nonetheless, these columns and essays attempt to define the boundaries of the definitions of cruel, ignorant, and foolish behaviors and actions and to place the living and breathing human in the abstract debate over the nature ethics and forms of government. While attempting these definitions there is also an exhortation to accept the incompleteness of any definition, to accept the irreducibility of the complexities of reality. There is an implicit proclamation to stop trying to systematize and categorize unnatural concepts and forcefully impose a meaning on the events and attitudes of the world. For this simple yet difficult-to-accept injunction alone it is worth reading these works.

[1] Eco, Umberto, and William Weaver. How to Travel with a Salmon & Other Essays. Trans. William Weaver. First edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1994. Print.

[2] Eco, Umberto. Five Moral Pieces. 1st U.S. ed. New York: Harcourt, 2001. Print.

[3] Eco was obsessed by lists and their power to be greater than the sum of their parts (that would be a different post altogether) and organized this just as I have here, though with explanations of each item. I have changed some of the wording to make it simpler and clearer.